Building Reflection into Your Learning Product

Summary

Embedding structured reflection into learning products empowers learners to deepen their engagement, apply insights to real-world contexts, and better self-assess their progress. Research indicates that carefully tailored and engaging reflection practices drive retention, critical thinking, and relevance. This article provides five innovative reflection practices supported by recent research, each designed to enrich your learning product.

Key insights:

Reflection and Feedback Synergy: Combining reflective activities with actionable feedback enables deeper comprehension and personal accountability.

Emotion-Driven Learning: Acknowledging emotional reactions to content aids memory retention and relevance.

Revisiting Key Concepts: Bookmarking content to revisit later supports spaced repetition, a proven method for improving long-term retention.

Applying Learning in Real-World Contexts: Reflecting on applying learning to one’s job encourages knowledge transfer, especially when shared with a manager.

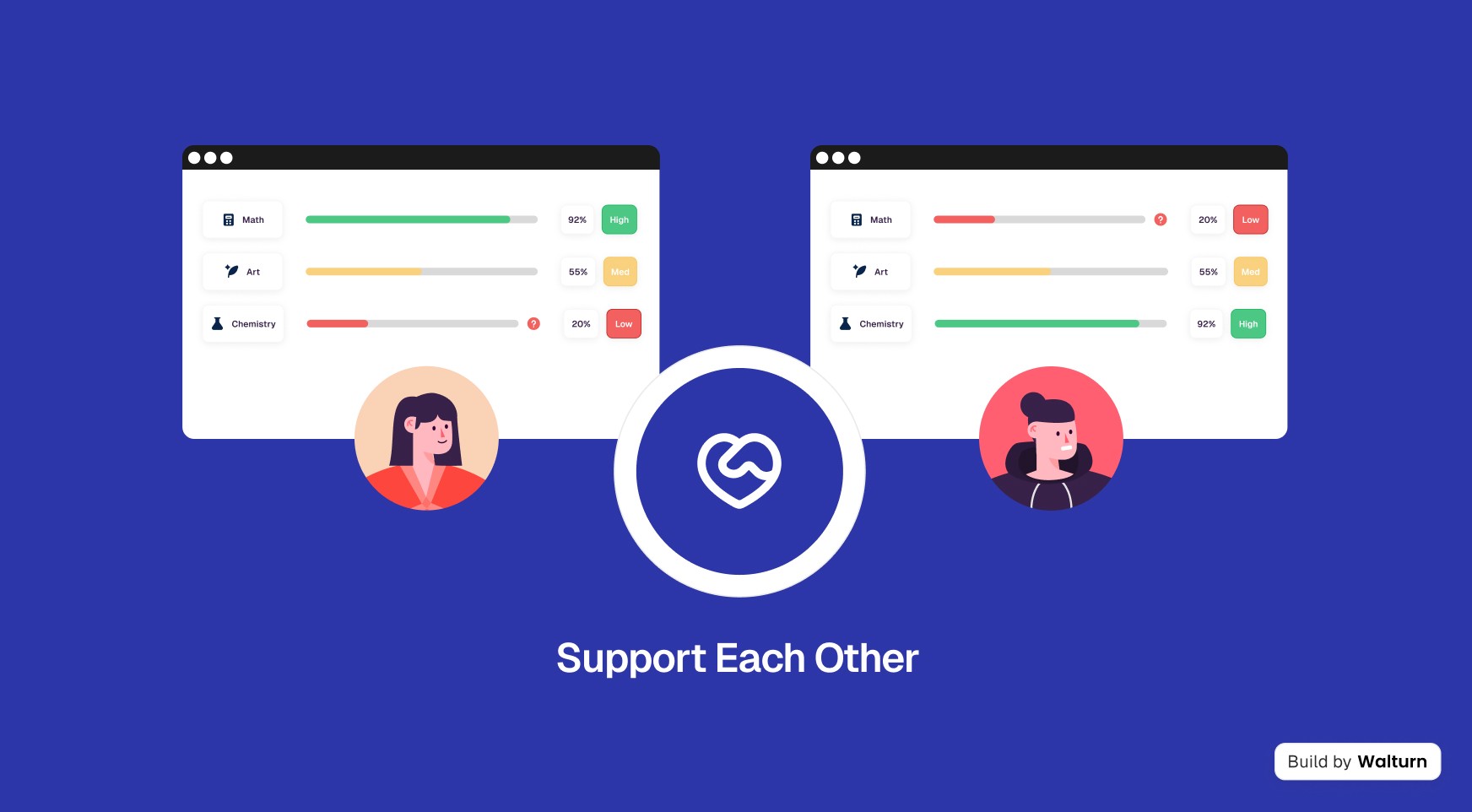

Peer Learning and Mentorship: Peer-reflection activities, where learners identify what they can share with and learn from others, can foster a supportive learning community.

Introduction

Feedback and reflection are fundamental for learners to assess their progress, understand their strengths, and address their challenges. When feedback is specific and actionable, it significantly enhances learning outcomes, as noted by Hattie and Timperley. Yet, without reflection, feedback alone may not be as impactful because learners need time and structure to internalize it. Thoughtful reflection helps bridge this gap by encouraging learners to analyze feedback and relate it to their personal learning goals.

Structured reflection activities that feel meaningful, not obligatory, have been shown to engage learners more effectively. Here, we detail five reflection practices for learning products, each one based on recent research and practical implementation strategies.

Five Practical Ways to Incorporate Meaningful Reflection

When we talk about reflection in digital learning experiences, free text prompts, and rating scales are usually the first that come to mind. However, despite robust evidence on reflection’s effectiveness as a learning tool, these activities often have quite a bad reputation among both learners and learning professionals for several reasons. They rarely feel relevant, or meaningful, for example. Crucially, they are almost never actionable or even retrievable, so learners hardly ever put significant effort into these activities.

However, with thoughtful design, it is possible to incorporate meaningful reflection into digital learning experiences. The key is to weave reflection into an ongoing, action-focused learning journey that has clear relevance to learners. Does this sound too abstract? Don’t worry, we share five practical approaches to incorporating meaningful reflection into your digital learning product below.

1. Add Emotional Reactions

Emotions can significantly impact how learners process and retain information. When learners are encouraged to acknowledge their emotional responses to content—whether they feel surprised, confident, or even challenged—it can help anchor new concepts more firmly in memory. Research in affective learning emphasizes that emotions associated with content can enhance both understanding and recall. Immordino-Yang and Damasio found that emotional responses to learning experiences activate regions of the brain associated with memory retention.

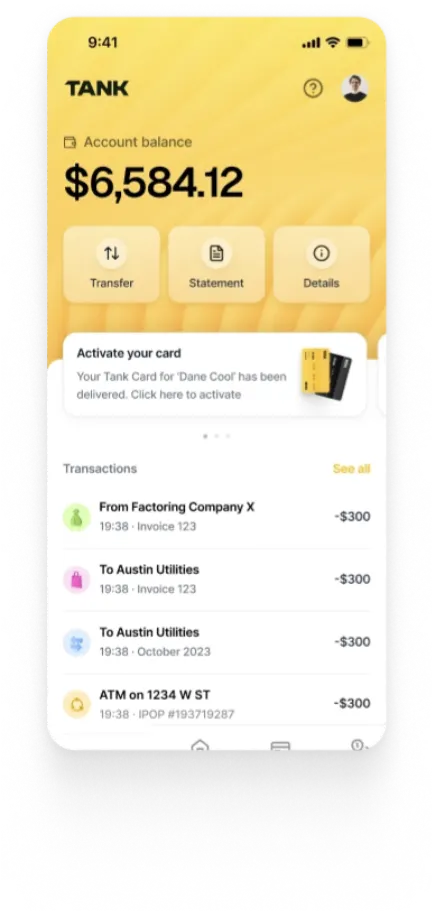

Further, by tracking learners’ reactions to specific content, you enable your learning designers to more effectively iterate on learning content and empower educators, or managers to address learning needs more accurately. Creating feedback loops and ensuring that reflections have meaningful relevance to learners’ or employees’ progress provides motivation to take these activities seriously. For example, imagine a case where a university math course is taught in a flipped learning model. Students take fundamental modules online, where they anonymously mark how they feel about the concepts covered: confused, surprised, confident. The math professor uses aggregated anonymous data to inform his live lesson plans.

How to apply it? Offer learners a quick way to note their emotional reactions to lessons, such as by enabling emoji reactions or color codes. Whether you use emojis or colors to denote emotions, make sure to clearly define what they mean to avoid confusing learners or misinterpreting data.

Considerations: This approach works best when learners understand how their responses will be used to optimize their learning journey. Understanding the connection between emotions and memory may also motivate learners to take these quick activities seriously.

2. Enable Bookmarking Content

The ability to bookmark specific pieces of learning content prompts learners to reflect on the relevance of the material and their level of understanding, which may positively impact learning outcomes. Adding a bookmarking functionality can also help you build out more effective spaced repetition or adaptive learning functionalities, taking into consideration learners’ needs.

While bookmarking, when effectively embedded into a learning journey, can be a powerful reflection tool, there are several pitfalls we need to consider. First of all, bookmarks are often used in informal settings to save interesting or important content, which users usually never retrieve. You will likely want your learners to bookmark differently than they usually do, so make sure to clearly define what learning bookmarks are for and how they will be incorporated into the learning journey. Second, it is likely that not all learners will be able to accurately assess which pieces of content are crucially relevant to them, and what it is that they need to practice more. Be sure not to rely solely on bookmarks when generating adaptive content and spaced quizzes.

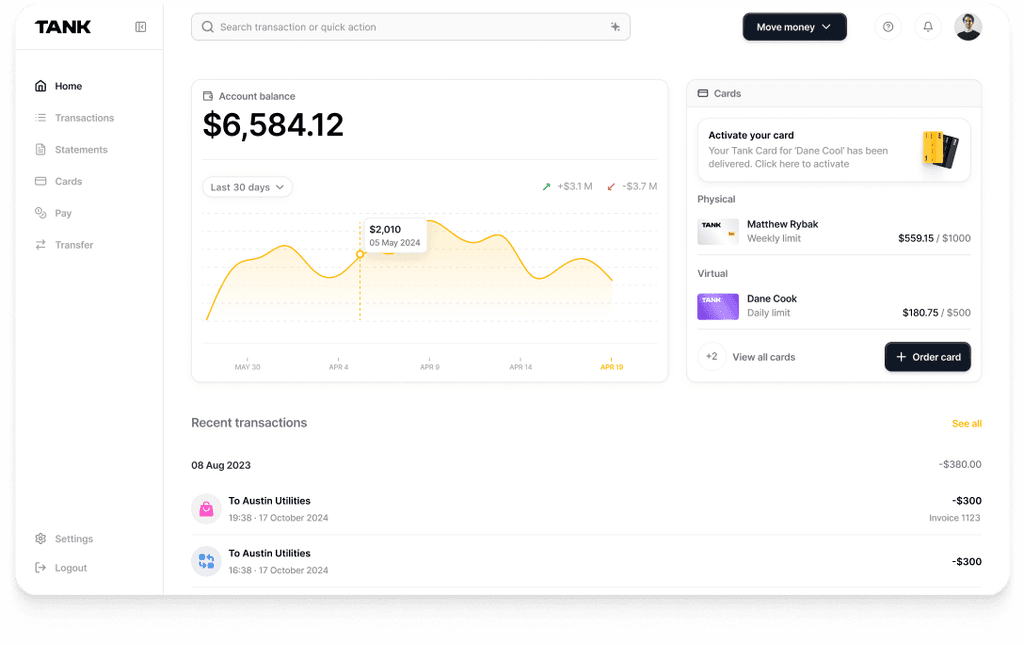

How to apply it? Integrate a bookmarking tool within your product where learners can mark important content. Make sure to enable learners to access their bookmarked content, and where appropriate, use bookmarks to inform adaptive learning journeys and spaced repetition quizzes.

Considerations: Bookmarking alone will not help if learners do not revisit their marked content or their content is disorganized. Save bookmarked content in an organized format and if you can, consider adding tags/allowing learners to tag their content.

3. Add Opportunities to Reflect on Real-life Implications

Reflection on practical application is essential for knowledge transfer, particularly when learners consider how they will use new skills in real-life contexts. Studies indicate that encouraging learners to link new knowledge to practical implications reinforces the relevance of learning and increases motivation.

These reflection activities can take various forms. However, due to their highly personal nature and depth, free-form responses are usually the most appropriate. This could mean a written response, or a short video or audio response. In some cases, prompting learners to create a presentation, proposal, or plan can also be highly effective. The key is to make sure that this activity is clearly linked to touchpoints outside of the digital learning experience in which they occur. If our audience is university students, we can tie this reflection to deliverables, such as a presentation or a project plan submission. In the case of corporate learning, we suggest sharing learners’ reflections with their managers and tying them into a professional development conversation or a tangible work deliverable.

Transparency is key - make sure to let learners know how their reflections will be used and with whom they will be shared. You can also consider allowing learners to pick who they want to share their reflections with and giving them the control to press ‘send’.

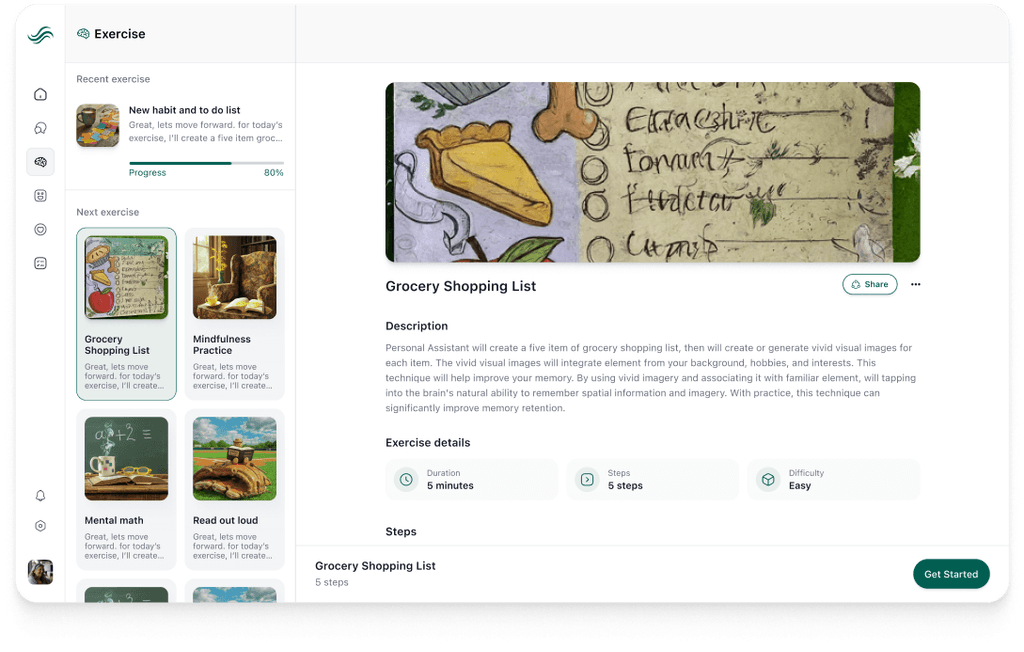

How to apply it? After completing major modules, prompt learners to think about how they can apply what they have learned in their current/future job or for solving a specific problem relevant to them. Make sure to provide clear instructions and guiding questions and if you use a free-form response activity, allow learners to pick how they want to submit their response - in written form, video, or audio. Enabling dictation and incorporating an AI chatbot to help learners’ thinking can further reduce friction.

Considerations: This type of reflection requires deep thought and real effort. Therefore, it is most meaningful when it is incorporated into a broader learning journey that may include coaching and/or the development of plans, presentations, or other deliverables. Use it in cases where learners have a considerable stake in achieving mastery.

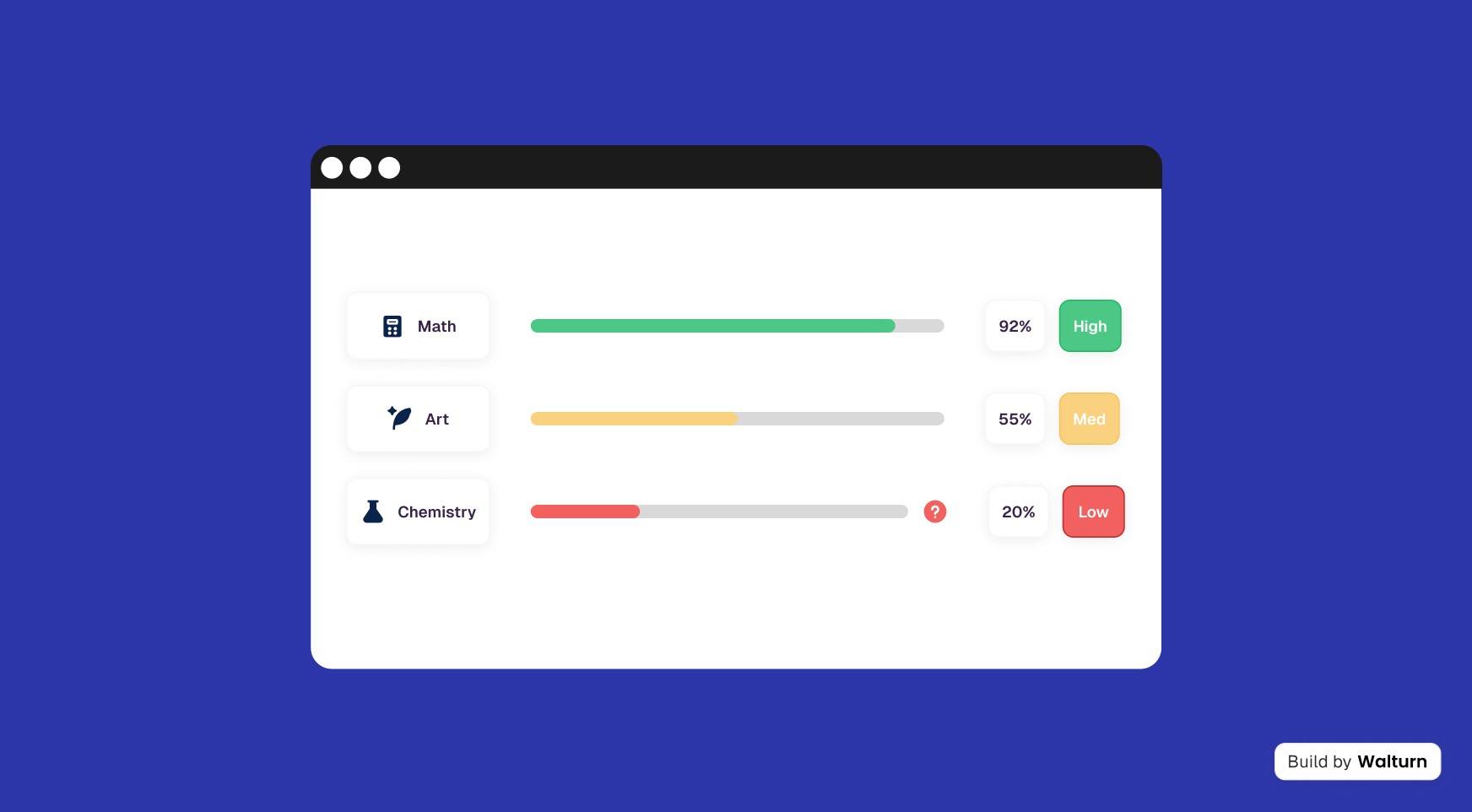

4. Ranking Confidence in Key Concepts

Having learners assess their confidence levels with specific concepts allows them to reflect on their strengths and areas for growth. Practising self-assessment has been shown to enhance metacognitive skills, which are critical for lifelong learning. Confidence ranking also enables personalized feedback; when learners identify lower confidence areas, additional support can be offered to strengthen these skills.

However, it is crucial to understand that confidence levels are not reliably indicative of an individuals’ knowledge or skills. Most individuals cannot objectively assess their strengths and weaknesses and actually, those with lower mastery are more prone to being overconfident. Therefore, the purpose of these reflection activities is not to conclude a learning journey, or to use it as evidence of impact.

To reap the benefits of self-assessment, we need to embed confidence ranking activities into a carefully designed learning journey. In cohort-based learning, confidence ratings can be mashed together with objective assessment results to inform tutors and educators on which areas of content need more attention and to call learners’ attention to potential discrepancies in confidence and skill levels, providing a great opportunity to further improve metacognitive skills. In settings where an individualized approach can be taken, confidence levels can be brought into individual tutoring, professional development programs, and coaching.

How to apply it? Implement a self-assessment feature for key concepts, where learners rate their confidence. Combine these ratings with more objective skill and knowledge assessments to inform further learning suggestions, such as extra resources, coaching, or practice opportunities.

Considerations: Without a clear understanding of how their ratings will be used and the right preparation to feel safe providing honest self-assessment, this activity may backfire or simply become ineffective. Psychological safety, and confidence that there will be no negative consequences if confidence levels are reported as low will be crucial, otherwise learners may report what they think is expected of them. If you have issues with psychological safety, and/or your learners come from diverse cultural backgrounds, some important context and honest, vulnerable statements from a trusted authority figure on what they used to struggle with and how reflection on their skills helped them grow may help, preferably on video.

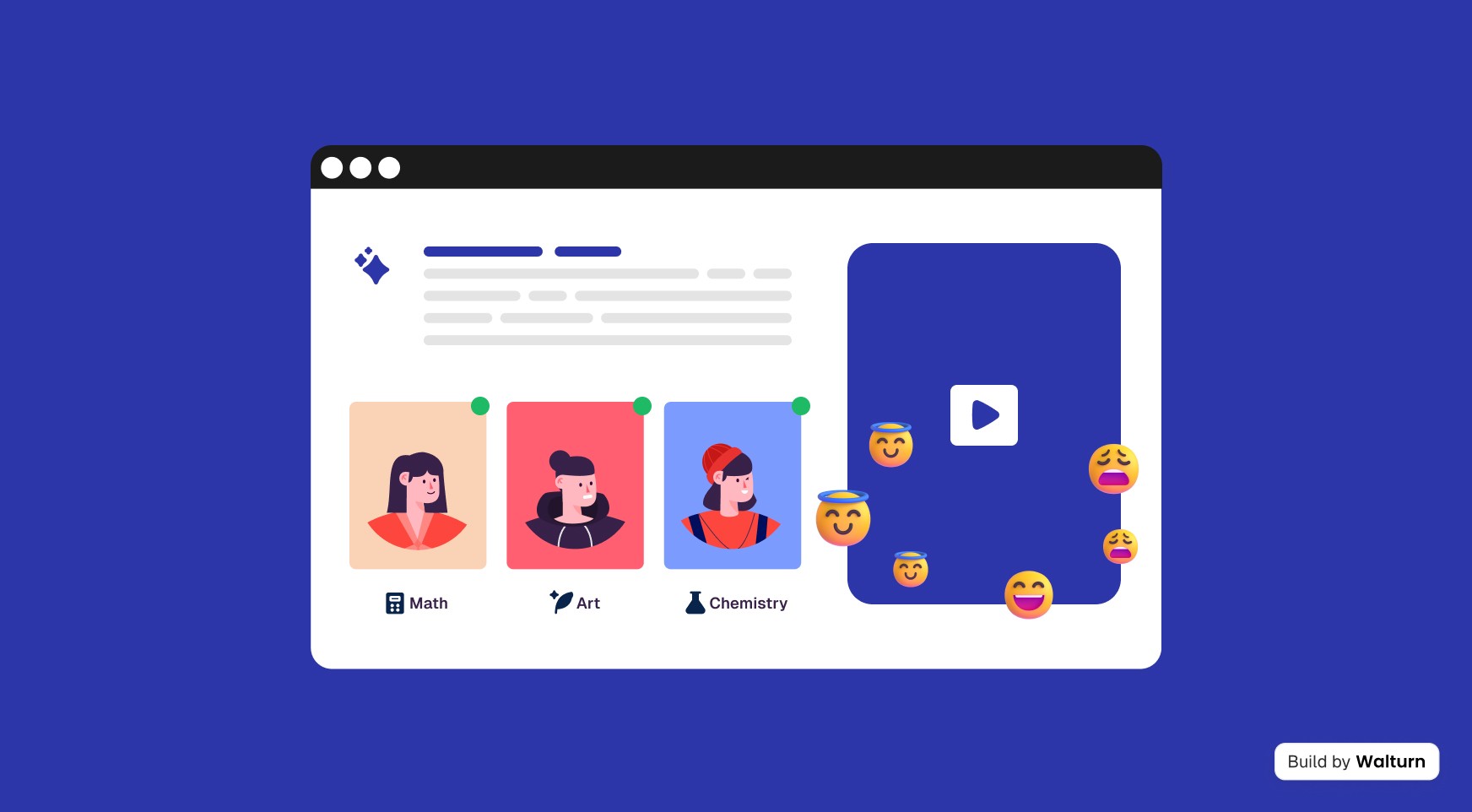

5. Reflecting on Peer Mentorship Needs and Skills

In collaborative learning environments, reflection on areas where learners need or can offer help promotes mutual support. Peer mentoring has been linked to improved self-efficacy and career interest, professional skills and resilience. Structured peer reflection encourages shared learning and mentorship, which fosters community and belonging. This may in turn boost productivity.

Here, too, establishing psychological safety and embedding it into a broader learning journey is key. Pair peers based on complementary sets of expertise, preferably in different roles and functions when it comes to professional skills. This is to avoid potential rivalry and to enable a risk-free, trusting relationship. It is also a good idea to link mentorship to specific, real-world milestones. For example, a salesperson with great presentation skills can mentor a software engineer, who is preparing to give an important presentation, or a graduate student in statistics can mentor a psychology student preparing to analyze and report on data collected for their thesis.

You can also experiment with a peer mentorship scheme for less conventional projects. For example, try reverse mentoring to help bridge communication gaps between team members from different generations and experience levels. You can also encourage peer mentorship in recreational skills or hobbies, such as financial planning, home renovation, and social media skills. This can open up new communication channels and unlock productivity and employee satisfaction in new, perhaps unexpected ways.

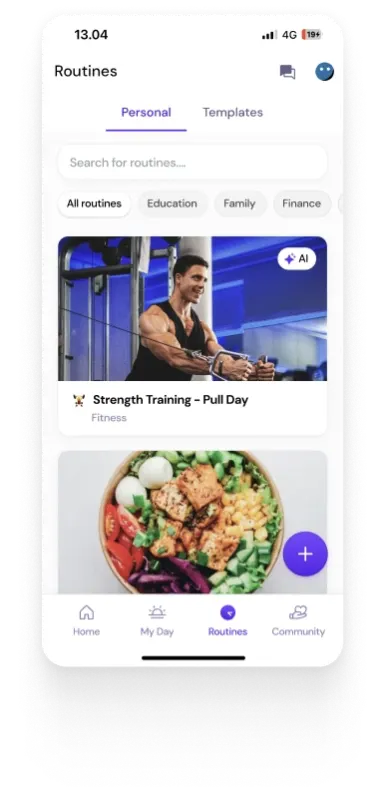

How to apply it? Allow learners or team members to mark areas where they feel confident and willing to offer help and those where they need help. Depending on the depth and importance of the topics included, consider including objective measures, and/or asking for peer and manager input before matching peers. It is often not an issue if mentorship is not mutual, or if someone only acts as a mentor, while others are just mentees. However, make sure to provide a clear framework and tie mentorship to real-world projects.

Considerations: For peer mentorship to succeed, a supportive environment is essential. Clear guidelines for respectful and constructive interactions can enhance comfort and participation. Further, consider the size of your potential mentor/mentee pool before implementing this reflection activity. Prompting learners to indicate where they need help but not being able to offer this help can erode trust and prove counterproductive.

Conclusion

Incorporating thoughtful reflection practices into learning products can transform the learner experience from passive absorption to active engagement, retention, and application. By using these innovative reflection techniques—rooted in recent research—you can foster a holistic, personalized, and effective learning environment that equips users for real-world success.

Build Reflection into your Product with Walturn

Reflection practices are powerful tools in your learning product’s toolkit. Are you building an EdTech product intending to optimize learning, and increase motivation and connections? Walturn’s expert teams are ready to guide you, as well as to design and implement features that focus on meaningful reflection. Get in touch today!

References

Anseel, Frederik, et al. “Reflection as a Strategy to Enhance Task Performance after Feedback.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, vol. 110, no. 1, Sept. 2009, pp. 23–35, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0749597809000430, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2009.05.003.

Bergman, Ofer, et al. “Out of Sight and out of Mind: Bookmarks Are Created but Not Used.” Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, vol. 53, no. 2, 21 Aug. 2020, pp. 338–348, https://doi.org/10.1177/0961000620949652. Accessed 17 Nov. 2021.

Chang, Bo. “Reflection in Learning.” Online Learning, vol. 23, no. 1, 2019, pp. 95–110, eric.ed.gov/?id=ej1210944.

Chen, Li, et al. “Factors of the Use of Learning Analytics Dashboard That Affect Metacognition.” International Association for Development of the Information Society, International Association for the Development of the Information Society. e-mail: secretariat@iadis.org; Web site: http://www.iadisportal.org, 2020, eric.ed.gov/?id=ED626746. Accessed 14 Nov. 2024.

Chen, Mei‐Rong Alice, et al. “A Reflective Thinking‐Promoting Approach to Enhancing Graduate Students’ Flipped Learning Engagement, Participation Behaviors, Reflective Thinking and Project Learning Outcomes.” British Journal of Educational Technology, vol. 50, no. 5, 27 May 2019, pp. 2288–2307, https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12823.

Hajian, Shiva. “Transfer of Learning and Teaching: A Review of Transfer Theories and Effective Instructional Practices.” IAFOR Journal of Education, vol. 7, no. 1, 1 June 2019, https://doi.org/10.22492/ije.7.1.06.

Harvey, Marina, et al. “A Taxonomy of Emotion and Cognition for Student Reflection: Introducing Emo-Cog.” Higher Education Research & Development, vol. 38, no. 6, 24 June 2019, pp. 1138–1153, https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2019.1629879.

Hattie, John, and Helen Timperley. “The Power of Feedback.” Review of Educational Research, vol. 77, no. 1, Mar. 2007, pp. 81–112, journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.3102/003465430298487, https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430298487.

Immordino-Yang, Mary Helen, and Antonio Damasio. “We Feel, Therefore We Learn: The Relevance of Affective and Social Neuroscience to Education.” Mind, Brain, and Education, vol. 1, no. 1, Mar. 2007, pp. 3–10, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-228x.2007.00004.x.

Liu, Ting, et al. “Peer Mentoring to Enhance Graduate Students’ Sense of Belonging and Academic Success.” Kinesiology Review, vol. 11, no. 4, 2022, pp. 1–12, https://doi.org/10.1123/kr.2022-0019.

Mazor, Matan, and Stephen M. Fleming. “The Dunning-Kruger Effect Revisited.” Nature Human Behaviour, vol. 5, no. 6, 8 Apr. 2021, pp. 677–678, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01101-z.

Rockinson-Szapkiw, Amanda, and Jillian L. Wendt. “The Benefits and Challenges of a Blended Peer Mentoring Program for Women Peer Mentors in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM).” International Journal of Mentoring and Coaching in Education, vol. ahead-of-print, no. ahead-of-print, 13 Nov. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1108/ijmce-03-2020-0011. Accessed 23 Nov. 2020.

Roll, Ido, et al. “Metacognitive Practice Makes Perfect: Improving Students’ Self-Assessment Skills with an Intelligent Tutoring System.” Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 2011, pp. 288–295, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-21869-9_38.

Ross, J.A. “The Reliability, Validity, and Utility of Self-Assessment.” ResearchGate, vol. 11, no. 10, 2006, www.researchgate.net/publication/279572878_The_reliability_validity_and_utility_of_self-assessment.